000_Talks Index.html

Homological Algebra

Classical homological algebra.html

Goal: provide some background for https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=etbcKWEKnvg!

What is Homological Algebra

- Why was it invented?

- What is it used for?

-

What are some easily understandable results that rely on it?

- Universal coefficient theorem?

- Used to prove Fermat’s Last Theorem (cohomology in relation to modular elliptic curves)

-

Where does it come up

- Stoke’s theorem: an integral over an \(n\)-dimensional region \(R\) of a manifold can be realized as an \(n-1\) dimensional integral over \({{\partial}}R\).

Content

-

Homology and cohomology

-

Used to detect \(n\)-dimensional holes, distinguishes manifolds. Given a manifold \(M\),

- A cycle is a closed submanifold

- A boundary is a cycle which is also the boundary of another cycle

- A homology class is an equivalence of cycles modulo boundaries

-

If such a class is nontrivial, this represents a cycle that is not the boundary of any submanifold - i.e. a hole.

- That is, a cycle would be considered a “trivial hole” if it is a boundary, and two “different” cycles would be considered the same hole if their difference is a k-boundary.

-

Easy example: all paths on \(S^2\) are homotopic to a point, not the case for \(S^1 \times S^1\).

- Note: \(S^n \neq \prod_{i=1}^n S^1\)

- Construction: a generalization of the Euler characteristic computation

-

Index by the integers, \(H_i\). We can look at the Betti numbers, \(b_i = \text{dim}_{{\mathbb{Q}}}H_i(X: {\mathbb{Q}})\)

- Give the number of \(n\)-dimensional cuts that must be made to disconnect a surface

- \(b_0\) is the number of connected components

-

\(b_1\) is the number of holes

- \(H_1(S^1\times S^1) = {\mathbb{Z}}\oplus {\mathbb{Z}}\)

-

\(b_2\) is the number of “2-dimensional” holes, i.e. an empty volume.

- Number of plugs you’d need to blow air into to inflate the object!

-

Used to detect \(n\)-dimensional holes, distinguishes manifolds. Given a manifold \(M\),

-

Modules

-

Most important classes

- Projective

- Injective

- Flat

-

Other nifty types (not mutually exclusive)

- Free

- Graded

-

Most important classes

-

Short Exact Sequences

-

Splitting of sequences

- Realize as an isomorphism

- Importance/use of exactness

-

Splitting of sequences

- Chain Complexes and maps

-

Tensor Product and Hom

- As an adjoint pair

- Derived Functors

-

\(\operatorname{Tor}\)

- Generalize the tensor product: \(\text{Tor}^R_0(A,B) \cong A \otimes_R B\).

- Formally: For a fixed module \(M\) over a ring \(R\), derived functor of \(M \otimes_R {-}\)

- Measures failure of tensor product to preserve exact sequences

-

Projective Resolutions

- Exists for any module \(M\), yielding an exact sequence \(\cdots \to Pn \to \cdots \to P_1 \to P_0 \twoheadrightarrow M \to 0\)

- Projective resolution of \(M\) can be used to calculate \(\text{Tor}_n^R(M,N)\) for all \(n\).

-

$

\operatorname{Ext}$- Derived functor of \(\hom_R(M, {-})\)

- Measures failure of \(\hom\) to preserve exactness

- Spectral Sequences

- Snake Lemma

What is homology?

“Homology” as a word just denotes some kind of study of “sameness”, which depends on what context you’re in.

It arose out of topology, where we are interested in studying when two manifolds are the “same” up to certain kinds of maps. Most generally, we look at continuous maps between spaces, but one could also look at smooth maps (differential geometry), or holomorphic maps (complex analysis).

This sameness can be useful, because you may end up working with some complicated, unknown sort of object, but maybe you’re only interested in the maps into or out of that object (for example, maybe smooth solutions to a differential equation on a manifold). If you know that there is another space that is the “same” up to smooth maps and much easier to deal with, you may be able to pull back results on the easier, well-known object into your complicated object and learn more about what you have.

When you just restrict to continuous maps, though, the discerning feature of spaces is their number of “holes”. We say that two spaces are homeomorphic if they are equivalent up to continuous maps, which you can alternatively think of as saying that one space can be continuously deformed into the other one. The classic example is that the torus (i.e. the surface of a donut) is equivalent to a coffee cup, due to the fact that both are missing a “hole”.

We have this intuitive notion, but since we are mathematicians, we need to make that precise! And of course, generalize. There are many different ways of defining what exactly an “\(n\)-dimensional hole” should mean, and homology started off as one of them that wound up being useful and quite successful.

How was homology first formulated?

There are many different ways to formulate the original homology, but they all roughly follow the same motto: “cycles mod boundaries”.

This originates from the world of manifolds, which are distinguished as topological spaces by their number of holes. One way to measure \(n\)-dimensional holes is to consider k-cycles on the manifold for \(1\leq k \leq n\), which are a bit like cutting instructions. A 1-cycle is a set of points to remove, puncturing the manifold. A 2-cycle is a loop you could take scissors to, and in general a \(d\)-cycle is a \(d\)-dimensional submanifold.

Manifolds may or may not have boundaries (picture: manifold with boundary), which means that cycles may have boundaries. So to measure the holes, we “mod out” by those cycles that are actually just the boundary of higher-dimensional cycles. (picture: quotienting as collapsing to a point). We call the equivalence classes generated by this quotient homology classes, and say that two cycles in the same class are homologous.

For example, on \(S^2\), every 1-cycle is homologous to zero - any path that is drawn can just be shrunk to a point, there is no obstruction. But on \(T\), there are two non-trivial one-cycles - a meridian and the equator. So we can use this formulation to distinguish spaces!

As it turns out, when this is formalized, we can lift these kinds of facts about manifolds and boundaries and cycles over to the world of algebra in a functorial way.

For a space \(X\) and every \(n\), one can form a group \(H_n(X)\) called the \(n\)-th homology group that encodes the information of what \(n\)-dimensional holes are in \(X\). We can assemble all of these together in a graded structure, something indexed by integers, and just generally look at \(H(X) = H_0(X) \oplus H_1(X) \oplus \cdots\) where the grading just indicates the dimension to extract.

Intuitively, \(H_0(X)\) tells you about the number of connected components, \(H_1(X)\) is the number of “areas” missing from \(X\), \(H_2(X)\) is the number of “volumes” missing, and so on. For these examples, we read off the number by how many times \({\mathbb{Z}}\) appears in the group.

Some examples:

\(H(S^1) = ({\mathbb{Z}}, {\mathbb{Z}}, 0, 0, \cdots)\) So we have 1 connected component, 1 one-dimensional hole, and that’s it.

\(H(B^2) = ({\mathbb{Z}}, 0, 0 , \cdots)\) So the filled in 2-dimensional ball has no holes.

\(H(S^2) = ({\mathbb{Z}}, 0, {\mathbb{Z}}, 0, \cdots)\) So we have one connected component, no one-dimensional holes, and one two-dimensional hole.

\(H_k(S^n) = \mathbf{1}[k = 0, n]\) In general, the \(n\)-sphere has one connected component and one \(n\)-dimensional hole.

Some Algebraic Background

In order to generalize and apply homology to other areas, we need to pull in a little bit of algebra. First, we need to talk about chain complexes. These can generally be formulated in what are called abelian categories, but we’ll stay a little more concrete than that for now.

Kernels, Cokernels, and Abelian Categories

Let’s get some terminology out of the way first, starting with something you may be familiar with: kernels.

You might remember this from linear algebra, so let’s work in the category of vector spaces for a moment. Given a linear map \(T: V \to W\), one interesting thing to look at is \(\left\{{v\in V \mathrel{\Big|}T(V) =0 \in W}\right\}\).

If \(V,W\) are finite dimensional, then after picking a basis there is a matrix \(A\) associated to \(T\), and so this is the set of all solutions to the homogeneous equation \(Ax = 0\).

We refer to this set as the kernel of \(T\). In the finite dimensional setting, this is equivalent to the nullspace of \(A\). Notice that \(T\) is injective (i.e. one-to-one) if and only if \(Ax = 0\) implies \(x = 0\), so the kernel is trivial. This holds in many categories!

Staying in the finite setting, we know that \(Ax\) lives somewhere in \(W\), and it is in fact a subspace. In a general setting, it’s not all of \(W\) - this would require that \(W\) and \(V\) had the same dimension (so \(A\) was square), and also that \(A\) had full rank (so \(A\) is not singular).

Note that if we were looking at groups, there is an entirely analogous procedure - \(T\) would instead be a homomorphism, and the image \(\text{im}~T\) would be a normal subgroup in \(W\).

In either case, we can always form the quotient \(W / \text{im}~T\), and this is what we’ll refer to as the cokernel.

In matrices, we just have

\(\ker A = \left\{{x \mathrel{\Big|}Ax = 0}\right\}\)

and

\(\text{coker}~A = \left\{{y \mathrel{\Big|}y^T A = 0}\right\}\)

Intuitively, both the kernel and cokernel carry a lot of information about the map.

The kernel measures how far the map is from an injection - this is because if the kernel is trivial, then the map is injective, so kernel size somehow measures “distance” from injectivity - larger kernels correspond less injectivity.

The cokernel measures how far the map is from a surjection. This is because if the cokernel is trivial, then \(\text{im}~ T\) is the entire target space, and thus \(T\) is surjective.

(Advanced note: in full generality, the kernel is defined in terms of a universal property. The cokernel is the categorical dual of the kernel, and satisfies a similar universal property. Duality is important!)

Exactness

Next let’s talk a little bit about exactness. Consider a diagram such as this:

\(0 \hookrightarrow A \xrightarrow{f} B \xrightarrow{g} C \twoheadrightarrow 0\)

where \(A,B,C\) are modules (or groups or rings or even vector spaces if you prefer), \(f, g\) maps between them as indicated, where left end of the sequence is the inclusion of the trivial module into \(A\) and the right end is a map sending every element to the single element of the trivial module.

We say this kind of sequence is exact if \(\text{im} f = \ker g\). What does this mean for elements? Well, if \(a\in A\), then \(f(a) \in B\). But if \(g\) is defined everywhere on \(B\), then it’s certainly defined for \(f(a)\), and \(f(a) \in \ker g\) means that \(g(f(a)) = 0\) in \(C\).

Equivalently, this just means that \((g\circ f)(a) = 0\) for every element in \(A\), or that \(g\circ f\) is the zero map.

One concrete benefit of this abstraction is that if we have

\(0 \hookrightarrow A \xrightarrow{f} B \twoheadrightarrow 0\),

then \(f\) is an isomorphism, and \(A \cong B\).

Another benefit is that if we have a diagram where an \(h\) exists such as this

\(0 \hookrightarrow A \xrightarrow{f} B \xtofrom[h]{g} C \twoheadrightarrow 0\)

where \(g \circ h = \operatorname{id}_C\) then (in an abelian category) this sequence is said to split, and \(C \cong B /A\). In other words, this is a generalization of the first isomorphism theorem.

In some instances, this also gives \(B \cong A \oplus C\) for some notion of “direct sum” appropriate to the category you’re working in.

Informally, when the sequence splits, this says that \(B\) is somehow a composite object, inside of which \(A\) and \(C\) are embedded.

Prototypes

Here are some places exact sequences naturally arise:

For \(N \unlhd G\) a group, \(0 \to N \to G \to G/N \to 0\)

For two distinct groups \(H, K\), \(0 \to H \to H\times K \to K \to 0\).

For two “related” groups, \(H, K\), where \(\phi: K \to\text{Aut}(K)\): \(0 \to H \to H \rtimes_\phi K \to K \to 0\)

The “extension” problem: given \(A, C\), and \(0 \to A \to* \to C \to 0\),

what can be filled in for \(*\) to generate an exact sequence? Any such \(*\) yields an “extension of \(A\) by \(C\)”. In the category of groups, we have a classification of all finite simple groups, so a general solution to this problem would yield a classification of all finite groups (!!!)

Nifty application: In vector spaces, every short exact sequence splits.

Let \(T: U \to V\) be a linear operator between vector spaces, let \(A = \text{nullspace}~T\), \(B=V\), \(C = \text{range}~T\), then take \(f = \operatorname{id}_V\) and \(g = T\). Then we recover the rank-nullity theorem from linear algebra, \(V \cong \ker T \oplus \text{im} T\) where \(\oplus\) is the orthogonal direct sum. (Note that this can also be interpreted as the fact that the map \(T\) factors into two other maps, one injective and one surjective).

Example: A SES that doesn’t split.

Take \({\mathbb{Z}}\xrightarrow{\times n}{\mathbb{Z}}\xrightarrow{\operatorname{mod}n} {\mathbb{Z}}/n{\mathbb{Z}}\), where \(n > 1\).

This is exact, since \(x \mapsto nx \mapsto 0\), so the composite is the zero map. But there is no map \(g\) that can invert the \(f(x) = x\operatorname{mod}n\) map, since \(x\in {\mathbb{Z}}\mapsto f(x) \in [0, n-1]\) means that \({\left\lvert {(g\circ f)(x)} \right\rvert} \leq n < {\left\lvert {{\mathbb{Z}}} \right\rvert}\), and the composite can’t be surjective. (E.g. this sequence throws away too much information to split!)

Commutative Diagrams

This one is easy - we say a diagram involving maps between objects if it doesn’t matter which path you take between two nodes - the composition of maps yields the same thing in the destination.

The Snake Lemma

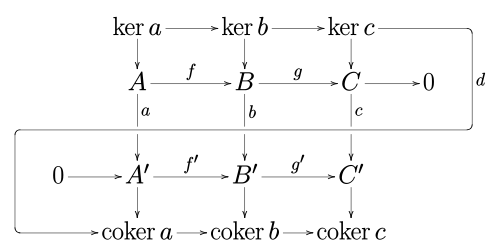

So now we can describe what is happening in the movie scene! (Note: this is probably the most advanced mathematics ever displayed in a movie.)

In any abelian category, we can consider things like commutative diagrams and exact sequences - so let’s do just this.

What this lemma does, in essence, is give you some information about what happens when you “transform” an exact sequence, or alternatively gives you a way to go back and forth between short and long exact sequences by a “connecting homomorphism”. The point of this is that the connecting map you obtain actually tells you about the existence of the related kernels and cokernels, providing valuable information about the intermediate maps.

So the setup is this - you have one exact sequence \(A,B,C,f,g\) and some transformation \(F = (a,b,c)\) that has three maps as its components, and the image of these happens to land on another exact sequence \(A', B', C', f', g'\).

As is almost always the case in algebra, we glean a lot of information from the kernels of maps, so one might ask about what’s going on with the kernels of \(a,b,c\), and it turns out they’re given by something like this:

What this says is that there is another exact sequence that you get for free, of the form

\(\ker a \to\ker b \to\ker c \xrightarrow{d} \operatorname{coker}a \to\operatorname{coker}b \to\operatorname{coker}c\).

Chain Complexes

When we have a sequence that is exact everywhere, we say it is a long exact sequence

A chain complex \(\left\{{(C_i, {\partial}_i}\right\}\) is a sequence, where each \(C_i\) is a module (or a group or vector space, if you want) and each \({\partial}_i\) is a morphism (or homomorphism), which are usually denoted the boundary maps or differentials, satisfying the condition \({\partial}_{n+1} \circ {\partial}_{n} = 0\) (so it is exact everywhere).

Diagrammatically, we have something like this:

\(\cdots \xrightarrow{{\partial}_{n+1}} A_{n+1} \xrightarrow{{\partial}_{n}} A_n \to\xrightarrow{{\partial}_{n-1}} A_{n-1} \cdots \xrightarrow{{\partial}_{2}} A_1 \xrightarrow{{\partial}_{1}} A_0 \xrightarrow{{\partial}_{0}} A_{-1} \xrightarrow{{\partial}_{-1}} \cdots\)

Every exact sequence is a chain complex, so this can be thought of as a generalization of exact sequences.

Often, you’ll see notation abused here, and people will refer to “the” boundary map \({\partial}\). Then the relevant condition is that \({\partial}^2 = 0\).

Homology From Chain Complexes

For some “nice enough” topological spaces \(X\), we can construct a set of building blocks in each dimension \(d\), usually referred to as \(d\)-simplexes, and build \(X\) as some combination of those. In fact, if \(X\) in an \(n\)-dimensional manifold, you only need simplexes of degree \(n\) or lower.

So for spaces that can be decomposed (or built, depending on your viewpoint) in this way, we can let \(C_n\) be the collection of all of the \(n\) simplexes. Moreover, some \(n\)-simplexes have \(n-1\) simplexes as boundaries, so we can define the map \({\partial}_n: C_n \to C_{n-1}\) that takes a simplex to its boundary. Since “boundaries don’t have boundaries”, it turns out that this defines a differential as defined above, and thus \(\left\{{(C_i, {\partial}_i)}\right\}_{i=1}^n\) forms a chain complex.

We can then take the \(n\)-th homology of \(X\) to be the generalization of “cycles mod boundaries”, and define \(H_n(X) = \ker {\partial}_n / \text{im} ~{\partial}_{n+1}\).4. Given a short exact sequence of chain complexes, we can always “pass to homology” in this way.

Applying the Snake Lemma

Theorem: Any short exact sequence of chain complexes induces a long exact sequence of homology modules.

Let

\(0 \to A \xrightarrow{f} B \xrightarrow{g} C \to 0\)

be a short exact sequence of modules. Then there is a long exact sequence in homology,

\(\to\cdots H_k(A) \xrightarrow{f^*} H_k(B) \xrightarrow{g^*} H_k(C) \xrightarrow{\delta} H_{k-1} (A) \to\cdots\)

A critical part of this is the fact that we get a map \(\delta: H_k(C) \to H_{k-1}(A)\), so we can work our way towards lower dimensions. (It also helps if \(A\) is somehow an easier object to work with)

Thinking of \(B\) as an “extension of \(A\) by \(C\)”, if we can find choices of \(B\) that fit the extension and make the sequence exact, we can glean information about all three objects together.

How is this used? In topology, the idea is that if we know how to glue a space together from small parts, and we understand the gluing maps well enough, then we have an avenue to understand the entire space (via its homology \(H_k(X)\) for all \(k\)).

One way this is explicitly used is to build the Mayer-Vietoris sequence, which allows us to compute the homology of two spaces whenever we know the homologies of both their union and intersection. (One usually takes these two spaces to be subspaces of a larger space we are interested in).

For example, take the torus \(T\) and cut it with a plane through the center into \(T = U \coprod V\). Then both \(U, V\) are cylinders (\(S^1 \times I\)), and \(U \cap V = S^1 \coprod S^1\), two disjoint circles. As seen earlier, we can compute homologies for spheres, and this gives us a way of combining that information to compute the homology of something a bit more complicated.